Tweeting and Nadia Bolz-Weber

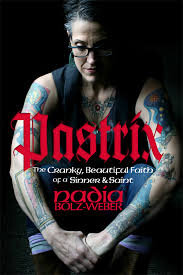

This week was trying out all sorts of stuff on Twitter. Learning it was not easy! I added more people to my list of those I'm following (about 50), mainly people in journalistic and religion reporting fields. Did a search for serpent handlers, but the only entries are by journalists who are covering the topic or by commentators making fun of those who practice handling. The handlers themselves aren't on Twitter. One of my requirements was to sign onto Vine, a Twitter subsidiary, which creates 6-second videos. You heard me: Six-second videos. Weird. I know. Here is the one I shot of planes at the Denver airport. I also had a class assignment to tweet about eight or nine different things and even interview people on the street. I got the majority of that done, but it wasn't easy. Trying to cram a quote into 144 words, as you'll see in my Broncos tweet, was a challenge. Intermixed with all this was a magazine assignment for which I got to fly to Denver last Friday for a write- up on Nadia Bolz-Weber, a most interesting Lutheran minister who is 6-foot-one, just wrote a very popular book called Pastorixis covered with tatoos and has a very untraditional congregation called House for all Saints and Sinners. While I followed her about the Parkview section of east Denver, I was sneaking in tweets of various locales, ie the coffeeshops she hangs out in, for this class assignment. Doing everything on one's iPhone is also awkward as all get-out as I'm wedded to my laptop and not to a tiny screen. Once I got all my photos shot and tweets composed, I put it all together in an ensemble called Storify that is like an Internet bulletin board of all your social media about one topic. I just joined Storify on Tuesday and am trying various ways to make it work.

Intermixed with all this was a magazine assignment for which I got to fly to Denver last Friday for a write- up on Nadia Bolz-Weber, a most interesting Lutheran minister who is 6-foot-one, just wrote a very popular book called Pastorixis covered with tatoos and has a very untraditional congregation called House for all Saints and Sinners. While I followed her about the Parkview section of east Denver, I was sneaking in tweets of various locales, ie the coffeeshops she hangs out in, for this class assignment. Doing everything on one's iPhone is also awkward as all get-out as I'm wedded to my laptop and not to a tiny screen. Once I got all my photos shot and tweets composed, I put it all together in an ensemble called Storify that is like an Internet bulletin board of all your social media about one topic. I just joined Storify on Tuesday and am trying various ways to make it work. While I was doing all this, I was holed up at a local Marriott where I'd type up my notes when not pursuing Nadia to various coffee shops, her CrossFit class, her home and then to a Thai restaurant where I had a few hours to pose questions. But 4 pm Saturday, we were both tired, so I took off to do some shopping at stores that don't even exist in Tennessee. It being sunny that Saturday, I thought I'd run up into the mountains for a quick ski Sunday morning. Well...I woke up at 6:30 a.m. Sunday to find a huge storm had blown in, several feet of snow was falling on I-70, traffic was already backed up and the wind chill factor at the ski area I was aiming for was -2. And so I chose to relax in my hotel room, finish typing up my notes, watch the Olympics and warm up in a hot tub. Later on I ran into a man in the hotel elevator who said he'd been stuck on the highway for eight hours. I did well to stay in Denver.And so now I'm back in Jackson as a few snow flakes lazily float through the air. One of our assignments this week was to read Clay Shirky, an NYU prof and media critic whose "Here Comes Everybody" is on our syllabus. He also operates a web site, where he posted this depressing look at high education late last month. I seem to have a talent for entering fields as they're cutting back. I was in journalism 30 years, the last five of which were filled with cutbacks and lay-offs. Am now in academia, which has seen better days. While sitting in the hotel room Sunday morning, I polished off three chapters with titles like "Everyone is a Media Outlet" (true, depressingly); "Publish, the Filter" and "Personal Motivation Meets Collaborative Production." The first chapter has to do with what happens to journalists when everyone thinks they can report on and publish news.

While I was doing all this, I was holed up at a local Marriott where I'd type up my notes when not pursuing Nadia to various coffee shops, her CrossFit class, her home and then to a Thai restaurant where I had a few hours to pose questions. But 4 pm Saturday, we were both tired, so I took off to do some shopping at stores that don't even exist in Tennessee. It being sunny that Saturday, I thought I'd run up into the mountains for a quick ski Sunday morning. Well...I woke up at 6:30 a.m. Sunday to find a huge storm had blown in, several feet of snow was falling on I-70, traffic was already backed up and the wind chill factor at the ski area I was aiming for was -2. And so I chose to relax in my hotel room, finish typing up my notes, watch the Olympics and warm up in a hot tub. Later on I ran into a man in the hotel elevator who said he'd been stuck on the highway for eight hours. I did well to stay in Denver.And so now I'm back in Jackson as a few snow flakes lazily float through the air. One of our assignments this week was to read Clay Shirky, an NYU prof and media critic whose "Here Comes Everybody" is on our syllabus. He also operates a web site, where he posted this depressing look at high education late last month. I seem to have a talent for entering fields as they're cutting back. I was in journalism 30 years, the last five of which were filled with cutbacks and lay-offs. Am now in academia, which has seen better days. While sitting in the hotel room Sunday morning, I polished off three chapters with titles like "Everyone is a Media Outlet" (true, depressingly); "Publish, the Filter" and "Personal Motivation Meets Collaborative Production." The first chapter has to do with what happens to journalists when everyone thinks they can report on and publish news. It used to be that journalists were trained and screened in or out through jobs and apprenticeships at smaller media that weeded out all but the most talented and persistent. If you lasted through the first five years at various small-town sweatshops, you then graduated to a Big Newsroom, which is what happened to me. After 6 1/2 years at two small newspapers, I was magically elevated to a post at the Houston Chronicle at the age of 30. Which is why, several years later, I was not amused to see large newspapers (where I eventually wanted to end up) hiring much cheaper people straight out of college and skipping those of us who'd gone through the training. I (and a lot of other babyboomer reporters) were never able to get to the top tier of newspapers for this reason. Most of my friends dropped out of newspapers and went into PR or academia. I hung out at the Washington Times until my 50s. But there was never any debate as to whether I was a journalist. These days, says Shirky, just about anyone with video capability and a blog platform is clamoring for the privileges that it took me and those like me years to earn.

It used to be that journalists were trained and screened in or out through jobs and apprenticeships at smaller media that weeded out all but the most talented and persistent. If you lasted through the first five years at various small-town sweatshops, you then graduated to a Big Newsroom, which is what happened to me. After 6 1/2 years at two small newspapers, I was magically elevated to a post at the Houston Chronicle at the age of 30. Which is why, several years later, I was not amused to see large newspapers (where I eventually wanted to end up) hiring much cheaper people straight out of college and skipping those of us who'd gone through the training. I (and a lot of other babyboomer reporters) were never able to get to the top tier of newspapers for this reason. Most of my friends dropped out of newspapers and went into PR or academia. I hung out at the Washington Times until my 50s. But there was never any debate as to whether I was a journalist. These days, says Shirky, just about anyone with video capability and a blog platform is clamoring for the privileges that it took me and those like me years to earn. Which is why journalists (who are trained) and bloggers (most of whom are not) are at such loggerheads with each other, as NYU prof Jay Rosen points out in this speech. His point is that bloggers are closer to what American media was like during its first 200 years: Opinionated, sometimes horribly wrong but always passionate. Only in the 20th century did objectivity (I'd call it professionalism) enter in, he says. Rosen thinks journalists need to get a life but I've been both journalist and blogger and my response to bloggers is that if you want the privileges of journalism, you need to accept its liabilities, ie lawsuits. The Washington Times had its own legal department to deal with all the people who wanted to sue us and every other newspaper has one too, or at least an attorney within close reach. I'm still waiting for inaccurate bloggers to get hit with some of the lawsuits that newspapers get threatened with. The only reason there's been so few of them is because bloggers don't have the deep pockets that newspapers have. (That sounds nasty, doesn't it? I really don't want anyone to be sued but I haven't enjoyed being edged out of an occupation partly because of things that bloggers do).

Which is why journalists (who are trained) and bloggers (most of whom are not) are at such loggerheads with each other, as NYU prof Jay Rosen points out in this speech. His point is that bloggers are closer to what American media was like during its first 200 years: Opinionated, sometimes horribly wrong but always passionate. Only in the 20th century did objectivity (I'd call it professionalism) enter in, he says. Rosen thinks journalists need to get a life but I've been both journalist and blogger and my response to bloggers is that if you want the privileges of journalism, you need to accept its liabilities, ie lawsuits. The Washington Times had its own legal department to deal with all the people who wanted to sue us and every other newspaper has one too, or at least an attorney within close reach. I'm still waiting for inaccurate bloggers to get hit with some of the lawsuits that newspapers get threatened with. The only reason there's been so few of them is because bloggers don't have the deep pockets that newspapers have. (That sounds nasty, doesn't it? I really don't want anyone to be sued but I haven't enjoyed being edged out of an occupation partly because of things that bloggers do). Shirky also spent an entire chapter on Wikipedia, explaining why such a chaotic mess somehow works. The book is a bit dated in that he doesn't include the reasons behind Wikipedia's pleas for contributions. He does have some interesting theories on "love" as manifested in the Internet. (Wikipedia is a Shinto shrine; it exists not as an edifice but as an act of love, he writes. Wikipedia exists because enough people love it and, more important, love one another in its context.) People work on Wikipedia entries for that reason, he says. Because everyone contributes, it's a pages magically self-correct themselves thanks to an invisible cadre of editors out there who have the free time to monitor their pet topics. But how does one attract the sort of person who builds up instead of vandalizes? I'm not sure he says.Anyway, I built a file about my trip in Storify. Click here to see it!

Shirky also spent an entire chapter on Wikipedia, explaining why such a chaotic mess somehow works. The book is a bit dated in that he doesn't include the reasons behind Wikipedia's pleas for contributions. He does have some interesting theories on "love" as manifested in the Internet. (Wikipedia is a Shinto shrine; it exists not as an edifice but as an act of love, he writes. Wikipedia exists because enough people love it and, more important, love one another in its context.) People work on Wikipedia entries for that reason, he says. Because everyone contributes, it's a pages magically self-correct themselves thanks to an invisible cadre of editors out there who have the free time to monitor their pet topics. But how does one attract the sort of person who builds up instead of vandalizes? I'm not sure he says.Anyway, I built a file about my trip in Storify. Click here to see it!