Visit to Iceland (finally)

Yes, almost two months have passed since I went to Iceland. Did you know that Icelandair names its fleet of planes after its many volcanoes? The one I took into Reykjavik was named Snaefells. We flew just to the west of Hudson Bay and over Greenland. I looked in vain for the northern lights, as two kids screaming behind me all night made sleep impossible. Early morning at the Keflavik airport (a good 30 miles west of Reykjavik) was a jumble of American flights arriving and European flights leaving. So, I headed out of the airport into the dawn air with that familiar parched lava-covered-in-moss landscape that makes up much of the Reykjanes peninsula on which the airport (and the famous Blue Lagoon) sit. The peninsula’s landscape “is a bit alien,” the Iceland Monitor says and that’s a fact.

Yes, almost two months have passed since I went to Iceland. Did you know that Icelandair names its fleet of planes after its many volcanoes? The one I took into Reykjavik was named Snaefells. We flew just to the west of Hudson Bay and over Greenland. I looked in vain for the northern lights, as two kids screaming behind me all night made sleep impossible. Early morning at the Keflavik airport (a good 30 miles west of Reykjavik) was a jumble of American flights arriving and European flights leaving. So, I headed out of the airport into the dawn air with that familiar parched lava-covered-in-moss landscape that makes up much of the Reykjanes peninsula on which the airport (and the famous Blue Lagoon) sit. The peninsula’s landscape “is a bit alien,” the Iceland Monitor says and that’s a fact. Avis (which had the grouchiest agent waiting on me at the airport) didn’t give me a copy of my contract until I called the next day twice to get it sent to me. Bu they did assign me a stick shift car, which took me awhile to remember how to use! (I remember a press trip I went on in Greece where the journalists had to go about in such cars and I was one of only 3 who knew how to drive those things). So off I went to Reykjavik at about 8 a.m. in the morning sun. My (very nice) AirBnB place atop a hill in downtown Reykjavik was close to Hallgrimskirkja, a massive church shaped like a rocket atop a hill overlooking the city.I wandered down the street to Reykjavik Roasters to get a slurp of coffee and a pastry to keep me awake and going until nightfall, then decided to head for Blafjöll, a ski resort about a ½ hour outside of Reykjavik. It was sunny (which can be a rarity in Iceland) and I figured I’d never again get the chance to ski there plus there’s nothing like speeding down a slope to stay awake). Off I went on a main highway out through the same volcanic landscape for about 20 miles. Then I headed up the mountain to the resort, which is not exactly suited for foreigners. It took me a few tries to find out where to rent skis, boots and a helmet, all of which set me back $51. It was another $27 for a 3-hour lift ticket (I didn’t get there until 2 pm) and there were no signs to various lifts plus several lifts were closed. In the States, there are people manning the lifts who can answer your questions. At Blafjöll, no one. I had to return to the ticket office to figure out certain basics. One problem was the high winds. To get to one of the few available intermediate runs, I went up on the ridge and nearly got blown off by the gale. I felt sorry for the kids up there who weighed far less than I did. The view of the top of Mt. Esja to the north was quite pretty. The visit ended with me tripping over the (hidden) step into the rental shop and falling to the floor, scattering poles and skis everywhere. They might want to put a ramp in that spot.

Avis (which had the grouchiest agent waiting on me at the airport) didn’t give me a copy of my contract until I called the next day twice to get it sent to me. Bu they did assign me a stick shift car, which took me awhile to remember how to use! (I remember a press trip I went on in Greece where the journalists had to go about in such cars and I was one of only 3 who knew how to drive those things). So off I went to Reykjavik at about 8 a.m. in the morning sun. My (very nice) AirBnB place atop a hill in downtown Reykjavik was close to Hallgrimskirkja, a massive church shaped like a rocket atop a hill overlooking the city.I wandered down the street to Reykjavik Roasters to get a slurp of coffee and a pastry to keep me awake and going until nightfall, then decided to head for Blafjöll, a ski resort about a ½ hour outside of Reykjavik. It was sunny (which can be a rarity in Iceland) and I figured I’d never again get the chance to ski there plus there’s nothing like speeding down a slope to stay awake). Off I went on a main highway out through the same volcanic landscape for about 20 miles. Then I headed up the mountain to the resort, which is not exactly suited for foreigners. It took me a few tries to find out where to rent skis, boots and a helmet, all of which set me back $51. It was another $27 for a 3-hour lift ticket (I didn’t get there until 2 pm) and there were no signs to various lifts plus several lifts were closed. In the States, there are people manning the lifts who can answer your questions. At Blafjöll, no one. I had to return to the ticket office to figure out certain basics. One problem was the high winds. To get to one of the few available intermediate runs, I went up on the ridge and nearly got blown off by the gale. I felt sorry for the kids up there who weighed far less than I did. The view of the top of Mt. Esja to the north was quite pretty. The visit ended with me tripping over the (hidden) step into the rental shop and falling to the floor, scattering poles and skis everywhere. They might want to put a ramp in that spot. Afterwards, I headed back to Reykjavik for a soak in one in their legendary collection of thermal hot pools. I went to the largest: Laugardalslaug, a complex in the western part of the city where I had my choice of pools at 38ºC, 40º, 42º or 44ºC. The hottest I could go was 42. There was also a salt-water pool that was packed. On a Sunday afternoon in April, it appeared mostly locals were there. The locker room was amazing; they gave you a bracelet that opened, then locked a locker door (good for all my ski clothes) without the mess of a combination lock. I was so jet-lagged, I nearly dozed off on a rock in one of the pools. Then I wandered about the touristy area downtown hunting for a cheap place to dine; finally settling on Jomfruin on Lækjargata, a Danish restaurant. By then I’d been up 36 hours at least. (Note - also visited Sundhöll Reykjavíkur and Vesturbæjarlaug pools later in the week).

Afterwards, I headed back to Reykjavik for a soak in one in their legendary collection of thermal hot pools. I went to the largest: Laugardalslaug, a complex in the western part of the city where I had my choice of pools at 38ºC, 40º, 42º or 44ºC. The hottest I could go was 42. There was also a salt-water pool that was packed. On a Sunday afternoon in April, it appeared mostly locals were there. The locker room was amazing; they gave you a bracelet that opened, then locked a locker door (good for all my ski clothes) without the mess of a combination lock. I was so jet-lagged, I nearly dozed off on a rock in one of the pools. Then I wandered about the touristy area downtown hunting for a cheap place to dine; finally settling on Jomfruin on Lækjargata, a Danish restaurant. By then I’d been up 36 hours at least. (Note - also visited Sundhöll Reykjavíkur and Vesturbæjarlaug pools later in the week). Monday was shopping day, which meant a stroll from my apartment down Skólavörðustígur and touristy streets such as Laugavegur, Bankastræti and Austurstræti, noting some of the Norse god names such as Odin's Street (Óðinsgata), Thor's Street (Þórsgata), Loki's Path (Lokastígur) and Freya's Street (Freyjugata). The weather was a carbon copy of Seattle's: moist with patches of rain and sun and in the mid-40s.Nice surprises included the Hlemmur food hall in the previously run-down Hlemmur district at the end of Laugavegur. There was a nice Thai food restaurant across the square and a vintage clothing shop next door run by the Red Cross. Food there was pricey (a bowl of tomato bisque for $16?!) but it was one of the places in town where you can get nice salads. That’s a switch from when I first visited Iceland 21 years ago where you couldn’t get restaurant salads anywhere.The afternoon and evening were spent talking with friends including Mike and Sheila Fitzgerald, longtime Assemblies of God missionaries to Iceland and founders of the radio station Lindin. The Fitzgeralds told me that because of tourists and AirBnB, the locals find it impossible to rent a place. A one bedroom would be about $1,500/month. Another friend, Ragnar Schram, took me up to the top of Perlan (a tower with a pearl-shaped roof to have coffee in its famous restaurant with city-wide views. He directs the Icelandic branch of SOS Children’s Villages, an international NGO that provides homes in 134 countries for orphaned and abandoned children.

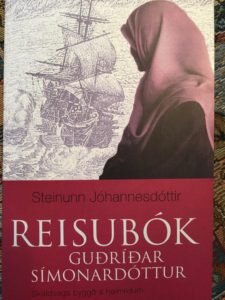

Monday was shopping day, which meant a stroll from my apartment down Skólavörðustígur and touristy streets such as Laugavegur, Bankastræti and Austurstræti, noting some of the Norse god names such as Odin's Street (Óðinsgata), Thor's Street (Þórsgata), Loki's Path (Lokastígur) and Freya's Street (Freyjugata). The weather was a carbon copy of Seattle's: moist with patches of rain and sun and in the mid-40s.Nice surprises included the Hlemmur food hall in the previously run-down Hlemmur district at the end of Laugavegur. There was a nice Thai food restaurant across the square and a vintage clothing shop next door run by the Red Cross. Food there was pricey (a bowl of tomato bisque for $16?!) but it was one of the places in town where you can get nice salads. That’s a switch from when I first visited Iceland 21 years ago where you couldn’t get restaurant salads anywhere.The afternoon and evening were spent talking with friends including Mike and Sheila Fitzgerald, longtime Assemblies of God missionaries to Iceland and founders of the radio station Lindin. The Fitzgeralds told me that because of tourists and AirBnB, the locals find it impossible to rent a place. A one bedroom would be about $1,500/month. Another friend, Ragnar Schram, took me up to the top of Perlan (a tower with a pearl-shaped roof to have coffee in its famous restaurant with city-wide views. He directs the Icelandic branch of SOS Children’s Villages, an international NGO that provides homes in 134 countries for orphaned and abandoned children. I spent Tuesday morning agonizing over the cloudy skies and whether to drive about 40 miles east to the small town of Hveragerdi and do the 3-km walk to the natural hot springs in the hills above the town. I finally drove out there and the rain clouds lifted and things got warmer BUT the trail was closed due to overuse by tourists. That sort of thing is happening more and more in Iceland, where the population triples in the summertime. So I visited the small geothermal park in town, then returned to Reykjavik. That evening, I had dinner with a newspaper editor I knew in town who - with his wife - had a lovely home east of the city. I was telling them of Steinunn Johnannesdottir, a female author I was trying to get ahold of. She had written about Guðríður Símonardóttir, wife of Hallgrímur Pétursson, an extraordinary 17th century couple from those parts. Hallgrímur wrote a lengthy series of Passion Hymns that are sung in Icelandic churches every Good Friday. He's like the country's poet laureate for the ages. Within 5 minutes, this editor had her on the phone, as everyone seems to be listed in the Icelandic version of our white pages. Turned out she lived about 2 blocks from my AirBnB. She and I agreed to meet.

I spent Tuesday morning agonizing over the cloudy skies and whether to drive about 40 miles east to the small town of Hveragerdi and do the 3-km walk to the natural hot springs in the hills above the town. I finally drove out there and the rain clouds lifted and things got warmer BUT the trail was closed due to overuse by tourists. That sort of thing is happening more and more in Iceland, where the population triples in the summertime. So I visited the small geothermal park in town, then returned to Reykjavik. That evening, I had dinner with a newspaper editor I knew in town who - with his wife - had a lovely home east of the city. I was telling them of Steinunn Johnannesdottir, a female author I was trying to get ahold of. She had written about Guðríður Símonardóttir, wife of Hallgrímur Pétursson, an extraordinary 17th century couple from those parts. Hallgrímur wrote a lengthy series of Passion Hymns that are sung in Icelandic churches every Good Friday. He's like the country's poet laureate for the ages. Within 5 minutes, this editor had her on the phone, as everyone seems to be listed in the Icelandic version of our white pages. Turned out she lived about 2 blocks from my AirBnB. She and I agreed to meet. So on a rainy Wednesday afternoon, I walked over to her home on a side street near Hallgrimskirkja. She served me coffee with lumps of sugar cubes and told me how, trained as an actress, she had been engrossed in stories of womens' empowerment. The role of reading the Passion Hymns during Good Fridays in Iceland is a well known role for any actress and it was through this that Steinunn heard of Guðríður and her amazing history. It's all based in the story behind some 1.5 million “white slaves” who were kidnapped from coastal cities all over Europe by Barbary pirates and taken to North Africa, most of them to never be heard from again.The summer of 1627 was a living hell for Icelanders, which is when 400 of them were snatched from their homes and thrown onto slave ships.The Westman islands (the islands off the southern coast of Iceland that got the brunt of the attacks) was massively de-populated by this heist, as their numbers were 1 percent of the Icelandic population at the time. There is a movie about

So on a rainy Wednesday afternoon, I walked over to her home on a side street near Hallgrimskirkja. She served me coffee with lumps of sugar cubes and told me how, trained as an actress, she had been engrossed in stories of womens' empowerment. The role of reading the Passion Hymns during Good Fridays in Iceland is a well known role for any actress and it was through this that Steinunn heard of Guðríður and her amazing history. It's all based in the story behind some 1.5 million “white slaves” who were kidnapped from coastal cities all over Europe by Barbary pirates and taken to North Africa, most of them to never be heard from again.The summer of 1627 was a living hell for Icelanders, which is when 400 of them were snatched from their homes and thrown onto slave ships.The Westman islands (the islands off the southern coast of Iceland that got the brunt of the attacks) was massively de-populated by this heist, as their numbers were 1 percent of the Icelandic population at the time. There is a movie about this called Atlantic Jihad you can find here or the YouTube version here. Ignore the warning that prefaces it. A lot of Icelanders died trying to defend their homes from these Moroccans or "Turks," as they were known to be back then. In 1629, the Turks attacked the Faroes, which are islands to the east of Iceland. Some 300 people died there including a 7-year-old son of a pastor who was horribly butchered. In 1631 these corsairs went to Ireland. Most Irish didn’t consider this a major historic event because they were also invaded by the British, Vikings and so on. But some 100 were kidnapped. The northern Europeans were easier prey than the Spanish, which had fortifications against them.“It’s only in Iceland that we have the documentation of this,” Steinunn said, “because so many people could read and write.” At the end of the film, Olafur Grimmson, the president of Iceland when the film was made, said his countrymen forgave the invaders; which tells me this event remained engraved in the racial memories of Icelanders if they were still talking about it nearly four centuries later.The kidnappings were also a declaration of war against the Danish, (who were running Iceland at the time) but the king didn’t have the money to go to war against Moroccans. There was also a raid in eastern Iceland where people were simply grabbed out of their homes and in Breiddalur, eastern Iceland, there’s still a place called “Turkish peninsula.” Some were freed by the Turks for the purposes of getting their home countries to fork out ransom for the rest. One Lutheran pastor was sent back from Algiers but had to leave his son behind. He got his wife freed but never saw his children again. As one of the hapless 400, Guðríður spent 10 years in what's now Algiers before the Danish government finally ransomed as many prisoners as they could. Only about 10 of them were located; the rest having died or disappeared into the slave camps or harems or God-knows-where.I was struck by this horrific story and how little it is known today. Americans don't realize that one of the first things the fledgling U.S. Navy did in the 1790s was build six ships that were used to defeat the Barbary pirates and send the U.S. Marines to North African shores. Steinunn's novel about Guðríður, Reisubók Guðríður Símonardóttir, came out in 2001 and was translated into French and German but Steinunn says she's been unable to get it into English. A New York filmmaker contacted her about her book, but after 9/11, he vanished. “So many people have wanted me to make a film or TV series about this,” she sighed, “but the subject matter is so delicate.” I told her there must be huge interest in this subject matter, but she felt she can't compete against the "Nordic noir" novels that are all the rage right now. I took notes, hoping to pitch her story to an American magazine. It's time it was told.

this called Atlantic Jihad you can find here or the YouTube version here. Ignore the warning that prefaces it. A lot of Icelanders died trying to defend their homes from these Moroccans or "Turks," as they were known to be back then. In 1629, the Turks attacked the Faroes, which are islands to the east of Iceland. Some 300 people died there including a 7-year-old son of a pastor who was horribly butchered. In 1631 these corsairs went to Ireland. Most Irish didn’t consider this a major historic event because they were also invaded by the British, Vikings and so on. But some 100 were kidnapped. The northern Europeans were easier prey than the Spanish, which had fortifications against them.“It’s only in Iceland that we have the documentation of this,” Steinunn said, “because so many people could read and write.” At the end of the film, Olafur Grimmson, the president of Iceland when the film was made, said his countrymen forgave the invaders; which tells me this event remained engraved in the racial memories of Icelanders if they were still talking about it nearly four centuries later.The kidnappings were also a declaration of war against the Danish, (who were running Iceland at the time) but the king didn’t have the money to go to war against Moroccans. There was also a raid in eastern Iceland where people were simply grabbed out of their homes and in Breiddalur, eastern Iceland, there’s still a place called “Turkish peninsula.” Some were freed by the Turks for the purposes of getting their home countries to fork out ransom for the rest. One Lutheran pastor was sent back from Algiers but had to leave his son behind. He got his wife freed but never saw his children again. As one of the hapless 400, Guðríður spent 10 years in what's now Algiers before the Danish government finally ransomed as many prisoners as they could. Only about 10 of them were located; the rest having died or disappeared into the slave camps or harems or God-knows-where.I was struck by this horrific story and how little it is known today. Americans don't realize that one of the first things the fledgling U.S. Navy did in the 1790s was build six ships that were used to defeat the Barbary pirates and send the U.S. Marines to North African shores. Steinunn's novel about Guðríður, Reisubók Guðríður Símonardóttir, came out in 2001 and was translated into French and German but Steinunn says she's been unable to get it into English. A New York filmmaker contacted her about her book, but after 9/11, he vanished. “So many people have wanted me to make a film or TV series about this,” she sighed, “but the subject matter is so delicate.” I told her there must be huge interest in this subject matter, but she felt she can't compete against the "Nordic noir" novels that are all the rage right now. I took notes, hoping to pitch her story to an American magazine. It's time it was told. By then it was time to show up for the opening reception for the Iceland Writer’s Retreat late that afternoon. This was my major reason for being in Iceland, as I'd won a partial scholarship to be there. It was situated about a half-mile from my lodging at a hotel near the domestic airport. We were all assigned five workshops along with a full day of touring "literary Iceland," as they called it. My first instructor was Pamela Paul, editor of the New York Times Book Review. Imagine having a staff of 24 for a book section! Most newspapers don't have anywhere near that luxury. Make your reviews entertaining, she told us. Don't just give them what they can get on Amazon. And you can show your biases as a reviewer because after all, the review is about your relationship with the book.The next day, I attended more workshops, including one by Icelandic writer Andrei Snaer Magnason whose best quote was to write what you want to write about, not what you think you should write about and the audience will be there. Lina Wolff, a Swedish writer, showed us how to create believable anti-heroes and how to help readers connect with these complex, ambivalent characters. One of the most famous anti-heroes in literature is Gollum from the "Lord of the Rings" trilogy. Tolkien helped us hate and pity Gollum at the same time. I'll be saying more about what I learned later.

By then it was time to show up for the opening reception for the Iceland Writer’s Retreat late that afternoon. This was my major reason for being in Iceland, as I'd won a partial scholarship to be there. It was situated about a half-mile from my lodging at a hotel near the domestic airport. We were all assigned five workshops along with a full day of touring "literary Iceland," as they called it. My first instructor was Pamela Paul, editor of the New York Times Book Review. Imagine having a staff of 24 for a book section! Most newspapers don't have anywhere near that luxury. Make your reviews entertaining, she told us. Don't just give them what they can get on Amazon. And you can show your biases as a reviewer because after all, the review is about your relationship with the book.The next day, I attended more workshops, including one by Icelandic writer Andrei Snaer Magnason whose best quote was to write what you want to write about, not what you think you should write about and the audience will be there. Lina Wolff, a Swedish writer, showed us how to create believable anti-heroes and how to help readers connect with these complex, ambivalent characters. One of the most famous anti-heroes in literature is Gollum from the "Lord of the Rings" trilogy. Tolkien helped us hate and pity Gollum at the same time. I'll be saying more about what I learned later. One of the highlights of our conference was the visit to the house of Guðni Th. Jóhannesson, the president of Iceland. His wife, Eliza, was the co-founder of the conference before he got elected. After she became Iceland's first lady, she continued her involvement with the conference and arranged for us to visit her home, which is known as Bessastaðir. It's on a peninsula just south of Reykjavik and all the writers had the greatest fun walking about it and exclaiming over some of the art pieces. Afterwards, three other of the female writers and I went to Laekjarbrekka, a lovely restaurant on Bankastraeti at a major intersection in Reykjkavik's touristy section. We managed to walk in without a wait, but during the high season, we wouldn't have had a chance.Another day, some of us went on a "literary tour" of Borgarfjördur, the region north of the capital. I've never read the work of Halldór Laxness, Iceland's sole Nobel literary prize winner, but we got to visit Gljúfrasteinn, his home in the country. A writer named Yrsa Sigurdardottir met us there and read us a creepy excerpt out of her new horror novel "The Legacy." Now I know what they mean by "Nordic Noir." We swept past waterfalls, the War and Peace Museum in Akranes, a hot spring in which our guide boiled some eggs and Reykholt, the home of 13th century chieftain Snorri Sturluson. Geir Waage, a Lutheran pastor who was beyond fascinating, spoke to us for a time on the history of the area and who Snorri was. I could have spent the whole day there, as there was a fabulous library there. And I could have spent even longer in Iceland, but home beckoned and pretty soon, I was on a plane home.

One of the highlights of our conference was the visit to the house of Guðni Th. Jóhannesson, the president of Iceland. His wife, Eliza, was the co-founder of the conference before he got elected. After she became Iceland's first lady, she continued her involvement with the conference and arranged for us to visit her home, which is known as Bessastaðir. It's on a peninsula just south of Reykjavik and all the writers had the greatest fun walking about it and exclaiming over some of the art pieces. Afterwards, three other of the female writers and I went to Laekjarbrekka, a lovely restaurant on Bankastraeti at a major intersection in Reykjkavik's touristy section. We managed to walk in without a wait, but during the high season, we wouldn't have had a chance.Another day, some of us went on a "literary tour" of Borgarfjördur, the region north of the capital. I've never read the work of Halldór Laxness, Iceland's sole Nobel literary prize winner, but we got to visit Gljúfrasteinn, his home in the country. A writer named Yrsa Sigurdardottir met us there and read us a creepy excerpt out of her new horror novel "The Legacy." Now I know what they mean by "Nordic Noir." We swept past waterfalls, the War and Peace Museum in Akranes, a hot spring in which our guide boiled some eggs and Reykholt, the home of 13th century chieftain Snorri Sturluson. Geir Waage, a Lutheran pastor who was beyond fascinating, spoke to us for a time on the history of the area and who Snorri was. I could have spent the whole day there, as there was a fabulous library there. And I could have spent even longer in Iceland, but home beckoned and pretty soon, I was on a plane home.